On the night of December 13, a day before she was supposed to fly down to Mumbai to get married to a Kashmiri Muslim man, Damini Bhajanka went missing from Guwahati.

A popular disc jockey who lives and works in Mumbai, her social media feed went silent, her phones were switched off.

For three months, her partner Waseem Raja Mughal searched for the 27-year-old woman. He filed a police complaint about her disappearance in Guwahati. He wrote to the National Commission of Women and filed a habeas corpus petition at the Gauhati High Court. “I went to everybody, from the police to the media for three months,” he told Scroll. “But nobody listened to me. They accused me of lying or of being mad.”

Bhajanka was finally rescued from a resort in Shillong on March 12, when she gave a written statement to the Meghalaya police, accusing her family members of kidnapping her and confining her against her wishes in a rehabilitation centre for drug addicts and alcoholics. “They did all these to stop my marriage with a Muslim man,” Bhajanka told Scroll.

The alleged abduction of an adult woman by her family, and confinement for three months to stop an inter-faith marriage – without the police taking any action – has raised eyebrows in Assam and elsewhere.

On March 15, Bhajanka filed a complaint at Mumbai’s Versova police station, asking for a zero FIR to be filed against her mother, brother, maternal uncle, cousin and his girlfriend.

A zero FIR can be filed at any police station, irrespective of the place where the alleged crime took place. The police station that registers the zero FIR has to forward it to the station that has jurisdiction over the matter.

More than two weeks after her rescue, no first information report has been filed by the police in three states – Assam, from where she went missing; Maharashtra, where she lived; and Meghalaya, from where she was rescued.

The day she went missing

Three days before Bhajanka, who goes by the name of DJ Dionne, was meant to get married at a marriage registration office in Mumbai, her mother Rekha Bhajanka called her home urgently.

She said she needed her daughter to sign “some important papers” related to a court case involving family property.

Bhajanka reluctantly agreed to travel to Guwahati on December 13, but booked a return flight for the next day. She said her mother knew that she had been in a six-year live-in relationship with Mughal and had agreed to attend the wedding.

She landed in the Assam capital at 12.13 am and sent her fiancé a message – the last time Mughal was to hear from her until she was rescued.

Bhajanka was picked up from the airport by her 25-year-old brother, Nishant Agarwal, and her cousin Gaurav Agarwal. They told her that they were going to the advocate’s office to sign the documents.

After a 40-minute drive, she realised that she had been brought to a rehabilitation centre in the middle of the city. Her phone and other belongings were confiscated.

A group of young women dragged her out of the car, as she shouted for help. “My cousin and brother threatened to beat me to death if I resisted,” Bhajanka told Scroll.

Bhajanka denied that she had any history of drug addiction or medical reports that said she was addicted to any substance. “I kept asking why I had been brought here,” she said. “They told me that my mother had given them permission to keep me there. I cried the entire night.”

She did not meet her mother for another two months, Bhajanka said.

The co-founder of the rehab centre, Bornali Baishya, refused to speak about Bhajanka’s allegations, citing patient anonymity. “We admit people with the consent of the guardian,” she told Scroll.

One of India's top DJ's was held in captivity for over 3 months in #Assam, with the full knowledge of the top police officials & media. Her crime: she wanted to marry a Kashmiri boy. Impossible you think in #NewIndia ? Read on:

— Nikhil Alva (@njalva) March 20, 2024

I met Waseem Raja during the making of Sarkaar Ki… pic.twitter.com/R3AILmMtb6

Habeas corpus petition

Thirteen days after her disappearance, Mughal decided to file an e-complaint with the Dispur police from Mumbai.

Any citizen can file such a complaint on a designated website. After verification by the concerned police station, the complaint is converted to an FIR.

In his complaint on December 26, a copy of which Scroll has seen, Mughal alleged that he had had no news from Bhajanka for two weeks.

“She was supposed to [perform at a venue] in Hyderabad on December 31, but her brother has returned the Rs 50,000 advance money yesterday on Damini's behalf, and he is not giving any information about Damini to the organisers or anyone,” the complaint said.

Mughal told Scroll that when he called officials at Dispur police station, they promised to help him – but took no action. “Then the sub-inspector and officer-in-charge blocked my calls and WhatsApp messages,” he said.

Asked about Mughal’s complaint, a police official at Dispur police station told Scroll, “It is a family issue and that’s why we did not give it much importance.”

He said that “there was a love affair between the complainant and the girl, Damini. But it seems the girl's family did not agree to their relationship.”

On January 3, Mughal filed a complaint with the National Commission of Women. On January 19, he filed a habeas corpus petition before the Gauhati High court, and declared Bhajanka’s mother Rekha Bhajanka, brother Nishant Agarwal, the director-general of police in Assam, the National Commission of Women and the officer-in-charge of Dispur Police as respondents.

In the high court, the matter was listed for hearing three times, but Mughal’s advocate sought adjournment for health reasons and then to file additional documents. The last hearing was on March 4.

@assampolice why did Damini Bhajanka's 2 mobile numbers have been off for 13 days now? y is her social media not active? y is her family cancelling her dj gigs on her behalf ? Ask Rekha 9864050101, nishant brother 7002614684, Manish uncle9864715037 @DGPAssamPolice @GuwahatiPol pic.twitter.com/zRzN1HYr1x

— Ali Mughal (@mughal82276) December 26, 2023

Days in the rehab

While Mughal was trying to coax the police to take action, Bhajanka was in distress at the rehabilitation centre.

“I was surrounded by drug addicts, alcoholics and criminals,” she told Scroll. “I would stay up all night afraid that any of them could come and hurt me physically.”

For over six weeks, she was not allowed to meet anyone from her family. After 40-odd days, her maternal uncle visited her. She said she pleaded with him to take her home. “He refused,” she said, “He replied with pride that they saved me from getting married to a Muslim man.”

By then, Bhajanka said she was a physical and mental wreck. “It was like spending time in a jail,” she said. “I was made to mop the floor three times a day, wash utensils, and clean the common toilet. I had suicidal thoughts, and once tried to cut my wrists.”

Finally, after two months, her mother and brother visited the centre.

“I held my mother tightly and cried a lot and pleaded and begged to take me out,” she said. “They told me that marrying Waseem would destroy my life and our family reputation. They left me there, crying.”

By March, news of her disappearance had begun to spread, and Mughal’s persistence had led to some coverage of her disappearance on social media and local news channels.

On March 11, she was asked to pack her belongings at the centre. Her mother Rekha, brother Nishant and cousin Gaurav picked her from the rehab centre. “But they did not take me home,” Bhajanka said.

They told her that Mughal had “trapped them in a huge conspiracy” and accused them of abducting her.

The next day, she was taken to a resort called Midhill Cottage in Shillong.

Her mother and brother asked her to make a video saying that she had been living happily with her family for the last three months. That, they said, would “save them from going to jail”.

Bhajanka sensed an opportunity. “They gave me my mother’s phone and quietly left,” she said. “I locked the room inside and I called my fiancé around 9.45 pm. I sent him a video asking to rescue me from my mother, brother and maternal uncle and cousin.”

Mughal alerted the Meghalaya police, who arrived at the cottage around 11.30 pm and rescued her around midnight.

The Meghalaya police officials treated her kindly, Bhajanka said. “But I was shocked that they let my brother and mother go, despite my written statement saying that they had abducted me,” she said.

Later, they dropped her at a friend’s home in Shillong. The next day, she took a flight to Mumbai.

Scroll sent queries to senior Meghalaya police officials. The story will be updated if they respond.

‘Do family members kidnap anyone?’

The disappearance and rescue of Bhajanka has left many questions about the role of the Assam police.

Bhajanka said that she called Assam police officials after her rescue, asking them to file an FIR against her family. “But they ignored me completely and disconnected the call,” she said.

However, Guwahati commissioner of police Diganta Barah dismissed the charges as “a family issue”. “A drug addict daughter has been kept in a rehab centre by her family members without informing others. Is that a crime?” he asked Scroll. “She is still not out of drug addiction and keeps uploading videos, saying that her family members kidnapped her. Do family members ever kidnap anyone?”

However, several women activists and advocates contested the police version.

“Prima facie, this case is not related to drug addiction,” said a woman activist, who does not want to be identified. “She was put into a rehab centre because of the disagreement over her marriage.”

Another activist pointed out that it is illegal “to restrain or abduct an adult woman and put her in a rehab against her will without a medical history.”

“Medical practitioners have to authorise that a person is a drug addict or the person had a history of addiction before putting someone into rehab,” the activist added. “In this particular case, the circumstances in which she was sent to rehab raise questions and doubts.”

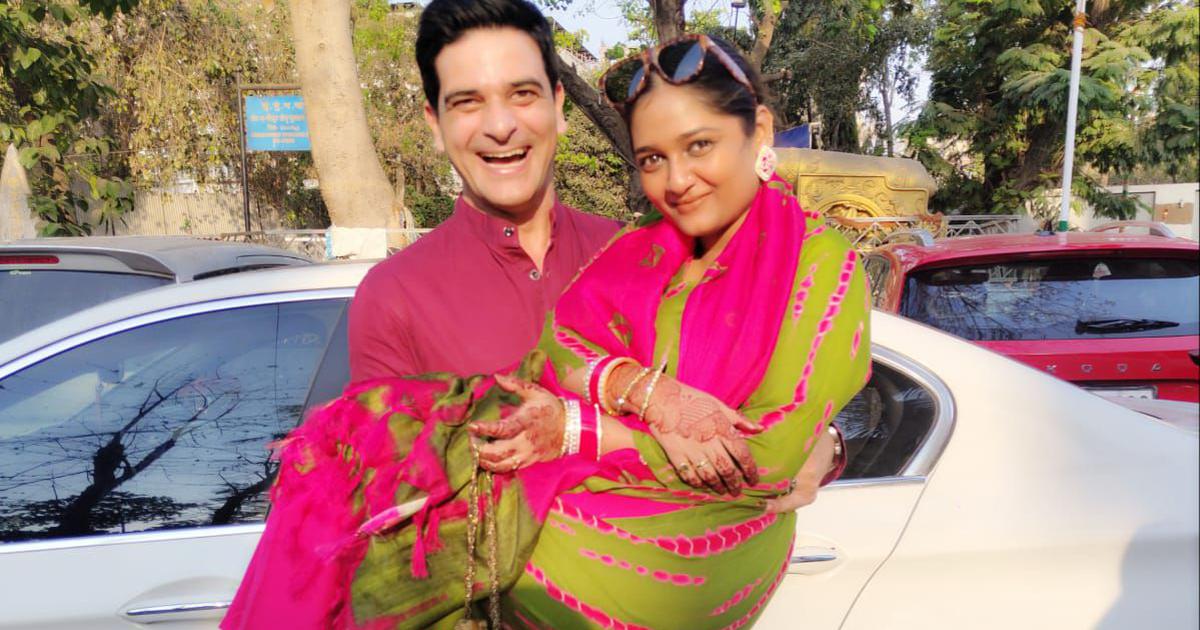

Bhajanka and Waseem got married on March 21 in Mumbai. “We will pursue the case till an FIR is registered and we get justice for the trauma and harassment they have caused us,” Bhajanka said.